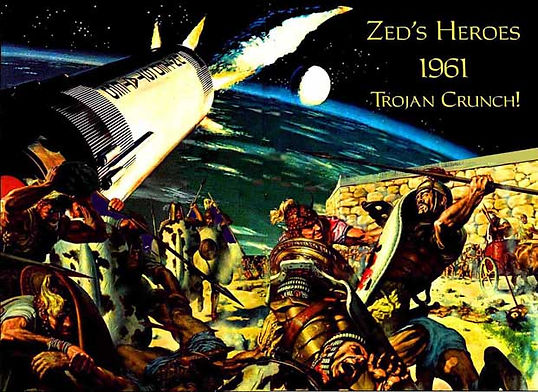

13. Trojan Crunch !

Sing, goddess, of the anger of Achilles, Pelues’ son, and the ruinous wrath that brought upon the Achaians innumerable woes... and it was bloody great. I loved it. The most difficult thing I had read so far and I remember how apprehensively I approached it, all that blank verse poetry and proliferation of words I didn’t understand. I persisted because it got hold of me and made me do so. And once the rip-roaring battle began and the defeated warriors bit the dust (literally), I was hooked. The Iliad became my new favourite book.

And Meriones slew Phereklos, son of Tekton Harmon’s son, whose hands were cunning to make all manner of curious work; for Pallas Athene loved him more than all men. He likewise built Alexandros the trim ships, source of ills, that were made the Lord of all the Trojans and himself, because he knew not the oracles of heaven. Meriones pursued, and overtaking him smote him in the right buttock, and right through passed the point to the bladder beneath the bone; and he fell to his knees with a cry, and death overshadowed him.

Then Meges slew Pedaios Antenor’s son, that was a bastard; yet goodly Theano nurtured him carefully like to her own children, to do her husband pleasure. To him Phyleus’ spear-framed son came near, and with keen dart smote him upon the sinew of the head; and right through amid the teeth the point of bronze cleft the tongues root. So he fell in the dust, and bit the cold bronze with his teeth.

Warrior after warrior, dozens of them, get their mini-biography before the death blow falls upon them, their slayer often delivering a stirring speech in fine poetry before or after the kill. Blows to the temple send helmets flying, severed limbs splash in dark pools of blood, a complete liver slips out and the butt end of a spear quivers as the heart it pierces thumps its final beats. They bite the dust, fall in their rattling armour, hollow hands clutching at life as it slips away from them, and darkness closes over them. Whereby the reserve warriors rush in to scavenge armour and weapons so that they may join the fray themselves. Back and forth between the black ships on the wine-dark sea and the windy walls of Troy, the battle rages, and the gods often join in even though they frequently fare as badly as the favourites they defend.

And the characters, those noble leaders Agamemnon and Priam, sulky Achilles and sturdy Hector, and the chief inspirers on both sides, Odysseus and Aeneas, and the all-slaughtering giants Diomedes and Ajax and… it goes on magnificently, the most vivid battle scenes ever depicted, and they still have few peers despite the innumerable men who have written of their wars.

Of course, not a word of it was true. Homer lived at least three hundred years after the Trojan War and had no written records to go on (which, had they existed, he could not have read anyway because he was blind)—it relied entirely on myth and legend. It mattered not one jot. Twenty-seven centuries later, I fought in the Vietnam War, between which conflict and the Trojan War there was not the slightest point of comparison. Nevertheless, what Homer wrote is just exactly the way it felt.

As usual, all the trouble is about men squabbling over women. It is the tenth year of the siege of Troy by the Greeks, and the boss-king Agamemnon - who has a bad habit of stealing other men's girlfriends, this time pinches Achilles' slave girl Briseis.

Achilles wants to kill Agamemnon but the Goddess Athena persuades him to be patient. So Achilles retires to a rock to sulk, but he reckons that he is the greatest of Greeks warriors and they can’t win without him. Not that they were winning with him. Really, at the bottom of all this is Apollo, who Achilles offended, and plots revenge. Achilles prevails upon his mother Thetis - who is also a goddess - to have a word with Zeus in his favour. She charms Zeus into agreeing, but Zeus is already in trouble with Hera for interferring too much in the war and so runs a double-cross - persuading the Greeks to attack on the one hand but warning the Trojans on the other. The result is a huge all in brawl

One hell of a battle ensues, with the giants Menaleus, Diomedes and Ajax wreathing hovac on the battlefield. Paris is almost killed but Aphrodite rescues him and carries him safely back to Helen’s arms. So intense is the fighting that even the Gods get wounded when they try to intervene on one side or the other. Aphrodite and Aeneas retire to get their wounds attended to.

The Greeks are about to give up, but Athena tricks them into fighting on. The battle of wits between the gods is as fierce as the clash of arms between the warriors.

Hector and Ajax fight each other throughout the whole day and have to call it off when night falls, mutually deciding that they ought to be friends.

The Greeks are forced back against their ships by the onslaught of Hector and they are all but defeated when Odysseus rallies them and they strike back.

The war is at a stalemate again, and once more the challenge is for someone to fight Hector. Achilles is the obvious choice but he remains grumpy and so his more artistic buddy Patrocles goes out in his place.

Patrocles fares well, putting the Trojans to flight and leading the Greeks back to the walls of the city, and Apollo, who favours the Trojans, has to wound Patrocles himself to stop him. Hector finishes him off.

Now Achilles is doubly angry, but no longer against Agamemnon - now he is after Hector.

Agamemnon, never a man to miss a political opportunity - he did actually sacrifice his own daughter Impigena to get a favourable winds to Troy in the first place - returns Briseis to Achilles, and now the great Greek champion is back in the fold. Thetis rearms Achilles and he fights and kills Hector, and then drags his body around the city behind his chariot.

While the shade of Patrocles is now freed to the underworld, King Priam must humble himself to Agamemnon and Achilles and pay the ransom to get Hector’s body back where it is mourned by Andromache.

The Iliad ends with both sides calling a truce so that they can jointly attend the funerals of the two great warriors.

It should be noted that the Iliad contains no mention of Achilles’ heel, although we know he can’t last with Apollo out to get him. Neither is there any mention of the wooden horse - that’s in Vigils’ Aeneid.