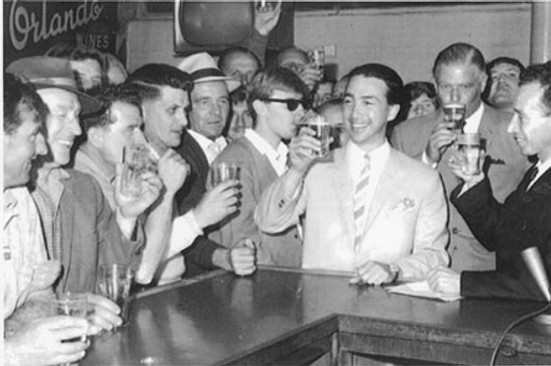

The 6 o’clock swill ended as dramatically as the old currency did not. Since the turn of the century, the Wowsers had ruled Australia and especially Melbourne, trying to force prohibition, building giant Coffee Palaces (which all eventually became pubs) but one of their last barricades was the restricted drinking hours, which meant a law demanding all pubs close at 6pm. The result was that every night (except Sunday when pubs couldn’t open at all), something resembling an ancient battle took place all over town. At about 5.30, workers and bludgers alike (predominantly males although the girls were increasingly getting themselves into the act) would descend upon the nearest pub until every public bar in the city was filled to capacity.

There were no tables or chairs, nothing but a sea of men with glasses in their hands which were not allowed to be empty. In the space of forty-five minutes, a full night’s drinking had to be done. The barmaid used a device called a pluto, which was a beer tap on a long house and just filled glass after glass at furious speed amid the roar and thunder of the demanding voices, and grabbed money from whoever’s shout it probably was.

It was divine chaos, and at 6 most drinkers would have a full round to gulp down. By law, the premises had to be vacated by 6.15 although it almost always took until 6.45 as last glass after last glass was poured down desperate gullets. Then it was onto the street where the emergency services raced at full capability to attend the thousands of fights and traffic accidents and drunken falls.

And then it ended, as the hours were expanded to 10pm, whereby while there were no fewer drinkers, fights and accidents, they were spread more evenly over the evening and, except on Fridays and Saturdays, most pubs only had a handful of drunks left by closing time. The advent of civilisation finally arrived.

A Norman knight Chrysagon de la Crue (Charlton Heston) comes to rule a bunch of Druids in a North Sea town, dominated by a weird, single tower keep. He is immediately besotted by a beautiful village girl Bronwyn (Rosemary Forsyth) after he saves her from an attack by his own dogs, which tear off her clothes and cause her to hide in the stream.

Heston is wounded defending the village from invaders and guarded and nursed by his sword-bearer Bors (Richard Boone). When he learns that Bronwyn is engaged to Marc (James Farentino), he asserts his right to the first night with the girl, but their shared passion is so intense that he decides to keep her. This enrages the superstitious Druids, and Heston’s brother Draco (Guy Stockwell) is sure the girl is a witch and has put a spell on the knight. In fact, Draco is jealous of his brother’s power and uses the situation to try and usurp him.

The brothers fight and Draco is killed, while Bors deflects the uprising by killing Marc, but Heston and Bronwyn remain together, an unsolvable problem. Bors, knowing his master is dying from the infection in his wounds, leads him away from the keep to make his peace with all.

The War Lord was wonderfully grim and a strangely realistic account of the times, the action well staged, the passions splendidly realised by the actors and the whole thing so thick with atmosphere that you could hardly cut it with Boone’s huge sword.