By the time we arrived, my mother had been moved up to the ward and was able to receive visitors. I entered, fearing what I was about to see, while Rosely hung back. But what I saw was far from what I expected. My mother was sitting up, and was having trouble locating words and there was a slight droop evident at the left corner of her lower lip, but her colour was good and she managed to arrange her face into a faint smile as I entered. Over in the corner, Howie had his nose in a comic book and was trying to avoid seeing anything in the room.

But it was Horrie who was the truly arresting figure. He sat by the edge of the bed, pressed as close as the structure would permit and held tightly to her hand. His head all but rested on her shoulder and every so often, when she could found the strength, she reached and touched his cheek comfortingly.

“She’s me girl,” Horrie was saying in a murmur. “I thought I’d lost you, I really did. You gave me such a fright, old stick.”

“There, there,” my mother said.

I wondered if Howie had brought any spare comics with him. And all the more so when repentant Rosely crept into the room. No one spoke. My mother simply raised her arms and Rosely fled into them and they hugged and began to weep. And Horrie threw his arms around both of them and joining in the tears.

I stared. I was floored. Had nothing I had known for the last twenty years of my life meant anything at all? Had I misunderstood my whole existence and everything in it so completely?

“Oh mum, I’m sorry. I’m so sorry,” Rosely was saying over and over.

“There, there, love. It wasn’t your fault,” my mother’s bent lips managed to construct.

“You gave me such a fright, old girl,” Horrie blubbered.

I stuck my hands in my pockets and went for a long walk.

“Big deal!”

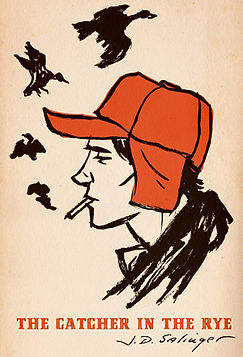

Sorry—it’s the only thing I can clearly remember from JD Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, but maybe that is appropriate—what Salinger is mostly famous for is the slimness of his contribution to literature. His is the laziest great author ever.

Catcher in the Rye was banned in many parts of the US, apparently because it encouraged independent thinking in youth. In fact this is the real basis of its fame—it came along just as post-pubescents were getting around to thinking about the iniquities of the world and the rebellion of the 1960s was in a fledgling state. As is the principle character here.

Holden Caulfield wags school and wanders through both New York and the book aimlessly, listless, opinionated and psychotic. Salinger wrote this little piece of teenage vernacular genius, demonstrated that he was Caulfield himself in his own lassitude, not bothering to try and write another novel, just a enticing few chapters of his next opus and a handful of hopelessly pretentious stories over two decades of extreme literary fame. Character and author both needed a good hard kick up the bum and never got it. The book very deeply expresses the sense of alienation of the time but offers no explanation. It’s just life and the best you can do is accept it, live with it, bad luck. Loved the book, hated the philosophy.

The book’s other claim to fame is the story that a chap named Mark Chapman got John Lennon to sign his copy of Catcher, just a few hours before he returned and shot the Beatle to death. Holden Caulfield going down the road his critics feared most.

It’s hard to judge its importance really—published in 1951 seems a generation too early, and these days it is more fashionable to put the youth rebellion down to Jack Kerouac. At the time it happened, they all reckoned it was Ken Kesey and Bob Dylan, and maybe Arlo Guthrie. I prefer to think it was all of them, and everyone else. After all, the bloke who really proved that prevailing values of Western Civilisation were a recipe for disaster was Adolf Hitler—but no one wants to give him credit for anything good and rightly so.