But we went to the hospital first, and I deposited Horrie and Howie at the Casualty Entrance.

“Ain’t you comin’ in to see how yer mum is?”

“It always takes ages,” I said. “I’ll go and see if I can get Rosely out first.”

“Leave her there. You oughta make sure mum’s okay.”

“She’s not going to get any better while her idiot daughter’s the clink.”

“Or yeah, I s’pose not. You gunna bring her back here then?”

“If I can. So I can show mum she’s okay.”

So I alone continued the rescue mission into the city. I found a convenient parking spot outside the Old Melbourne Gaol where, I knew, they had hung Ned Kelly. I crossed the road and walked into the stark lobby of Police Headquarters—D24 as it was called.

“You’ve got my sister here,” I declared to the desk sergeant. A long slow process of explanation followed, whereby the sergeant made a call and returned.

“They gave them a warning and let them go,” the sergeant explained. “The hotel didn’t want to press charges.”

“Decent of them.”

“Letting them off easily if you ask me.”

“Depends on your definition of easily,” I smiled, thinking of what lay ahead.

I walked out into the feeble sunlight of a drab midwinter day and wondered what to do next. It was only two city blocks south and one east to the Southern Cross Hotel—I could even hear the tumult of voices from where I stood. I thought about the huge posters of the Mop-top Musicians—the Four Hairmen of the Apocalypse as one panic-stricken journalist called them—that profusely adorned my sister’s bedroom walls. She had been so excited by them that she had allowed me to enter her room to marvel at them. She had even acquired four wig stands—for she worked as a hairdresser—and had the appropriate identical black wigs on each, arranged in their rightful order of John, Paul, George and Ringo. I knew that even though none of the four faces she drawn looked the least bit like that namesakes and she had been obliged to add their names, so there could be no confusion.

Yes, there wasn’t any doubt about where she would have gone next.

…Javert remained motionless for several minutes, gazing at this opening of shadow ; he considered the invisible with a fixity that resembled attention. The water roared. All at once he took off his hat and placed it on the edge of the quay. A moment later, a tall black figure, which a belated passer-by in the distance might have taken for a phantom, appeared erect upon the parapet of the quay, bent over towards the Seine, then drew itself up again, and fell straight down into the shadows ; a dull splash followed ; and the shadow alone was in the secret of the convulsions of that obscure form which had disappeared beneath the water.

Victor Hugo had so impressed me with The Hunchback of Notre Dame that when I saw a thick paperback with his name on it, I bought it right away and set myself to wade in. Never mind that I would pronounce the name in literal Australian until embarrassingly corrected years later. I had an Uncle Les who was a farmer and complained continually… but I knew it was French and wouldn’t be anything like that. Les Miserables was very long, and I fizzled not too far into it—seemed to be some dull stuff about some mayor in some town who was nice to everyone…

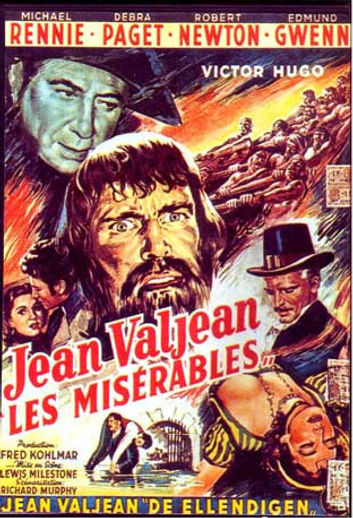

That might have been the end of the matter had not the 1951 version of the movie turned up on television, starring two of my favourite actors, Michael Rennie and old Long John himself Robert Newton. Now critics assure me that this is the poorest version of the piece ever done but they can go stick their collective heads in a bag, because it did the job for me as few movies had since 20,000 Leagues under the Sea. And I can tell you there have been a couple of recent versions that are much much worse. I thought the movie and Rennie quite terrific and tore through the book with frenetic enthusiasm as a result. Maybe what it really proves is that even a bad movie of a great book has its uses.

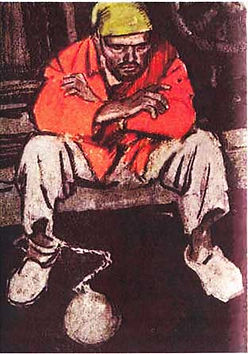

In 1815 at Toulon, a convict named Jean Valjean is released from the galleys. He was sentenced to 5 years for stealing a loaf of bread but served much longer because of his many attempts to escape. Only a man of his immense physical and mental strength could have lasted so long in the galleys. A kindly priest takes him in, whereby Valjean steals the silverware but when the police catch him, the priest declares he gave Jean the goods. Years later, Jean has spun his ill-gotten gains into a fortune making necklaces.

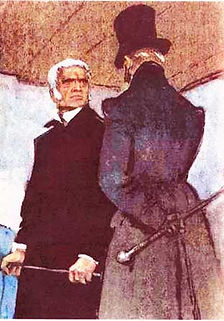

Valjean has become the respectable Father Madeleine and is much loved in the town for his good works, but Inspctor Javert is watching when Jean lifts a heavy wagon to save a man trapped under it, and is sure that only the escaped convict Jean Valjean has such strength. He has been pursuing Valjean relentlessly for years. But he is frustrated when another man, Chapmanthieu is arrested and identified as Valjean.

As a consolation, Javert arrests a prostitute named Fantine who was forced to this life by being an abandoned mother. She was forced to sell her baby daughter, Cosette, to the cruel innkeepers Thenardier who charge exobitantly for her keep and work the child like a beast. Fantine is dying of TB and Valjean plans to reunite mother and daughter.

Valjean cannot allow another man to be convicted of his crimes and so goes to Arras and confesses he is Valjean. He escapes and, after Fantine dies, and another arrest and escape, is declared dead. Under a new name, he goes to the Thenardiers and takes the now 8 year old Cosette. They go to Paris, however Javert is still on Jean’s tail but once more they escape.

They hide in a convent when the gardener turns out to be the man Valjean saved from under the cart. He hides Valjean in a coffin which, due to a mix up, is duly buried. The gardener only just manages to dig him up in time. Cosette is enrolled in the convent school and Valjean is taken on as a gardener himself. Thus another decade passes, for Valjean still has much wealth stashed away.

It’s now 1831 and a young man named Marius, aristocratic son of a hero of Waterloo, has joined the revolutionaries. Each day in the gardens, he sees a beautful young woman in the company of a 60-year-old man. It is of course Valjean and Cosette, and the youngesters, after too many complications to relate in this space, fall in love.

But the revolution is underway and Marius mans the barricade, Valjean is there to keep him out of trouble, and so is Javert once more on the scent. But Javert is exposed and as the battle rages, Valjean is given the task of shooting Javert. Instead he frees him, and then finds the wounded Marius and escapes with him, through the sewers of Paris.

Javert cannot arrest Valjean, torn between his duty and his debt to the man. He throws himself off a bridge into the Seine.

But there’s still a hundred pages to go of confusion before the lovers are married and Jean Valjean finally finds contentment, whereby he has the good grace to fall ill and die.