My only moments of relief from the ongoing nightmare of the factory floor was when, each day at ten o’clock, I would be despatched to the nearby shop to buy the custard tarts and sticky buns for those who wanted them with their morning tea. In addition, I would collect similar orders for the office staff, telephoned through earlier by Mrs Gizzard, and deliver them to the office.

The office was placed up the stairs at the front of the Assembly building, behind a thick wall that shielded it from the noise and heat. It was a small oasis of civilisation and sanity amid the madness, where people spoke softly, politely, and sometimes even smiled.

“Thank you, Zed,” plump Mrs Gizzard would say as I placed the box of goodies on her desk. “Did you have enough money?”

“The change is in the box,” I would say, always speaking too softly for her to hear me at first and then, when she demanded I repeat it, did so far too loudly causing all the office staff to stop and stare at me.

“I am become Death, Shatterer of Worlds.”

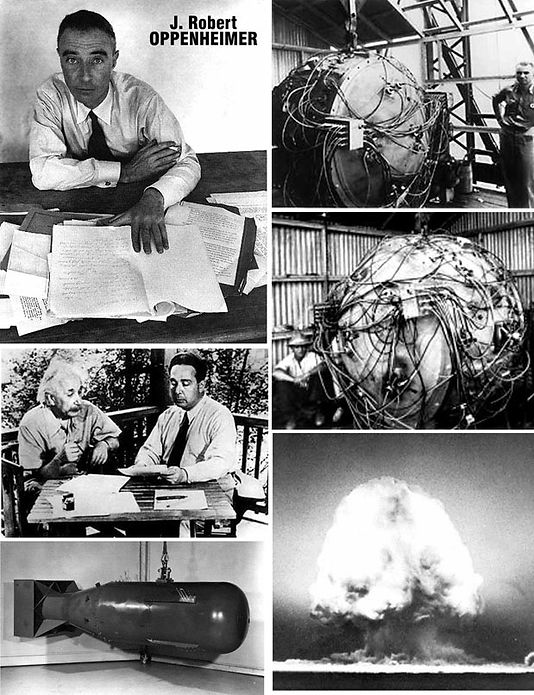

Thus spake J. Robert Oppenheimer when he first detonated an atomic bomb. He was quoting the Hindu Bhagavad-Gita.

Brighter Than a Thousand Suns by Robert Jungk was published in 1958 (English translation) and it is interesting to note that the story and how it is told in these more enlightened times is little different from when this radical and controversial work appeared—written by a German because no Englishman or American would have dared. But the controversy was lost on fourteen year old me—indeed I am rather shocked to realise that I got through such heavy material at all at that age.

I remember that it was the terrific title that grabbed me—I was sure I was in for science fiction of the Verne/Wellsian type. No—how the atom bomb was developed. Well okay. I was fascinated by atom bombs, as we all were by any subject that was never touched upon in the classrooms. My existing knowledge on the subject was confined to Walt Disney’s severely propaganda-ised TV piece, Our Friend the Atom, in which the dangers were only referred to vaguely and Hiroshima not considered at all. Atom bombs I reckoned were wonderful, especially because our side had the best ones. The British had been exploding them in Australia which made us all feel terribly important.

Halfway into Jungk’s book, my whole world began to skew. When I got to the stuff at Los Alamos and the expressions of fear and horror of the scientists at the initial tests, my brain suffered a fission of its own. As Enola Gay flew toward Hiroshima, the dread seeped into my very being and I suddenly began to look in the sky at every aeroplane that passed, not in awe but in fear of what it might be carrying and what if they dropped it on me.

And then came the final act of the persecution of Robert Oppenheimer, whom the US government branded as a traitor because he tried to persuade them not to use his own creation. The tragedy of this remarkable man, possibly the most disastrous life ever lived, brought me to tears.

Of course, it soon faded. The nightmares went away and the fear of planes gave way once more to excitement. My faith in the honesty and wisdom of governments returned—if in somewhat shaken form—but the wonder had gone from nuclear weapons and it would stay that way. And whenever an issue would arise in which the actions of politicians were called into question, I would remember Oppenheimer. Usually, no one would know what I was talking about. For years I suspected I was the only person in my world who knew these things and I kept my mouth shut out of fear of making a fool of myself. Certainly, there was nothing in the classroom, nor on television, nor in movies, that suggested the knowledge was shared. In October 1962 when the reality of nuclear war finally came home to everyone else, I was not in the least surprised.