All of this inactivity allowed me a great deal of time for reflection, and what I reflected on mostly was how on earth was I able to put up with all that boredom. That I was exacting my own little personal revenge upon the criminal insurance business was only a fraction of the answer. I needed the money, sure, but that wasn’t enough.

Some people live for their work—they are the lucky ones—but most work for a living. The means of earning the money can be ignored if the manner in which you spend it offers sufficient pleasure. But I didn’t have a life to spend my money on. I still lived at home with my parents, and had outgrown all my previous friends and wasn’t doing very well finding new ones. At home I watched television. In the evenings I hunted down people to have a beer with but all too often ended up in the bar on my own.

Something needed to be done about all these things, and, rather amazingly, I did just that.

Albert DeSalvo has a problem. Arrested in 1967 by Massachusetts police in the room of a woman he does not know, he is unable to account for why he is there. Moreover, he has been having the most horrific nightmares of murdered women. Police are sure that they have enough evidence to convict him being the ‘Green Man’, who has bound and assaulted over 300 women in four states, but Albert is seeing dead women.

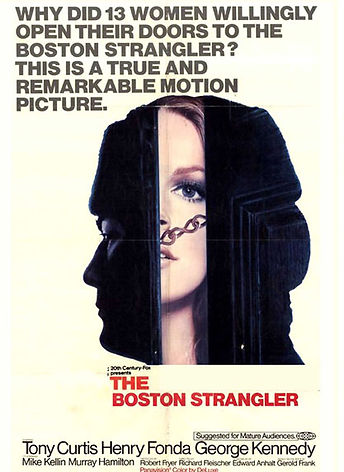

Gerald Frank’s factual account of these matters—The Boston Strangler—is harrowing enough and has a lot of additional information, but it is the startling movie made by Richard Fleischer on the subject that was more effective. Tony Curtis shocked everyone with a brilliant performance as DeSalvo—in fact he had proven he was a good actor a number of times before (in The Sweet Smell of Success, for instance) but his usual performances were so bad everyone kept forgetting that. Henry Fonda is the police psychiatrist who, in a kindly, sympathetic way leads him through the horror of his past. On the surface, DeSalvo is a decent man, a family man, until his covert life begins to emerge from the shadows, even for him. The film is all split screens and confusing images to suggest powerfully the chaotic state of DeSalvo’s mind, but slowly the truth begins to evolve. He is the monster who strangled 13 women in Boston. For Fonda, the trick is not so much to get a confession—the police already have sufficient evidence against him to put him in an asylum for life—but to persuade DeSlavo to face his true self. Inch by inch, the awfulness creeps into DeSalvo’s conscience mind, and with it the final, terrific realisation of his own dreadful crimes.

A split personality leading to two criminals in one body, but oddly DeSalvo was only ever convicted of being the ‘Green Man’, since there was never any corroborative evidence beyond his own confessions that he was also the ‘Boston Strangler’.