In just eight hours after I was lifted out of the war zone in the aftermath of my last fire-fight and landed back in civilization—culture shock was hitting hard. I was an entirely different person, but the world I had once inhabited so comfortably had not changed even slightly and wasn’t about to adjust. Next day I wandered, still in uniform because none of my civilian clothes fitted anymore, and feeing very vulnerable without my rifle to hand, searching the city for something, anything, new and different. And, as if Stanley Kubrick was aware of my predicament, it waited for me around the corner in Collins Street. There stands the Regent Cinema, a monument to crass thirties architecture, Hoyts gothic, but it really imitated the sorts of movie palaces being built by Fox studios and others at the time. Valiantly defended by the National Trust from the greedy hands of developers, it’s still there and still a primary theatre, and the extravagant interior decoration is all part of the show.

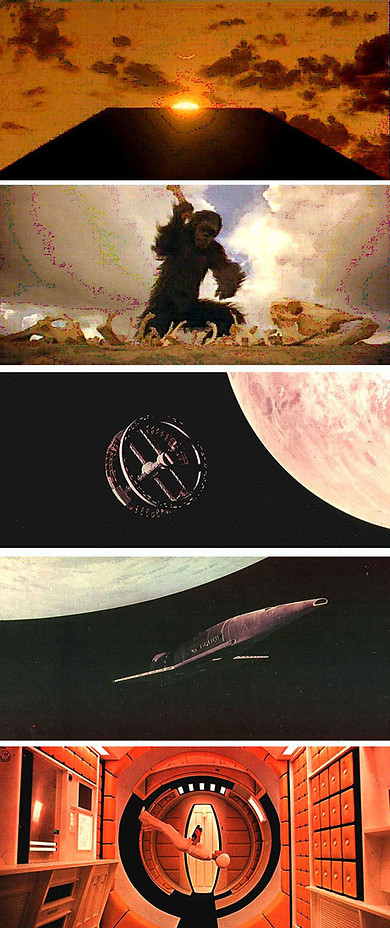

But in 1968, technology was already challenging it, and in its basement, they had set up the Cinerama system with its giant wrap-around screen. And there stood a group of men in spacesuits, gazing at a strange black obelisk. I knew what this was. In an MGM promotional film I saw a year or so earlier, there was a brief image of the great wheel of the space station in orbit, and a dream of Kubrick that I had shared all my life; to make a serious, proper science fiction movie, with superior special effects. And so it had come to pass.

I saw it in awe, too amazed by the space ships to absorb anything else, walked straight out to the box office and bought a ticket to see it again next session. Overnight, I dreamed of it, mulled over it, and went back next day to see it again. It didn’t just take my mind off the war, it turned my whole world on its head.

Behind every man now alive stand thirty ghosts, for that is the ratio by which the dead outnumber the living. Since the dawn of time, roughly a hundred billion human beings have walked the planet Earth.

2001: A Space Odyssey, by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. It was all I dreamed of. The opening view of Earth rising over Moon as The Sun rises over Earth, all to Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, was enough to dispel the legacy of a hundred B movies This, I knew, was way beyond my dreams.

Open the pod-bay doors, Hal. Hal, open the pod-bay doors.

I’m sorry, Dave. I can’t do that.

When I first saw the film, I was awed and entranced and didn’t understand it at all, didn’t try, just went along for the ride, and wisely so. I didn’t know then that Kubrick had deliberately left bits out of the film to help make it incomprehensible and mysterious. I have no criticism of him for this—he was trying, I believe successfully, to create impressionistic cinema, and put down for all time the conjecture that movies were not art. There are many other film makers before Kubrick to whom they wish to attribute the conversion of film into an art-form, but since 2001, no one has dared make the contrary suggestion that it is not art, as they often did before him.

Be that as it may, as much as I enjoyed the art, still I was anxious for answers. I saw it three times in a week, puzzled over it deeply, worked it out despite Kubrick’s attempt to manipulate my thoughts. I wasn’t sure that I was right, but I argued my case furiously with everyone I knew. And, as it happened, Arthur C. and I agreed in the end.

As Isaac Asimov did with Fantastic Voyage, so here Clarke wrote the novel at the same time as the film-script, and once I learned that, I pounced on the book like a tiger and gulped it down. Clarke left in the bits Kubrick left out and I understood it perfectly and marvelled. I knew I could safely leave science fiction in Hollywood’s hands from then on.

My whole character can be summed up by this. Yes, I enjoyed the Kubrick version with the explanation obscured for its pure aesthetic effects, but I needed to know the answers as well, and so I also read Arthur C. Clarke. Here, then, is the point of departure between the partners—the moment when the film goes one way with the sequence junkies loved most, and the book quite another.

He had been hanging above a large, flat rectangle, eight hundred feet long and two hundred wide, made of something that looked as solid as rock. But now it seemed to be receding from him; it was exactly like one of those optical illusions, when a three-dimensional object can, by an effort of will, appear to turn inside out—it’s near and far sides suddenly interchanging.

That was happening to this huge, apparently solid structure. Impossibly, incredibly, it was no longer a monolith rearing high above the flat plain. What had seemed to be its roof had dropped away to infinite depths; for one dizzy moment, he seemed to be looking down into a vertical shaft—a rectangular duct which defied the laws of perspective for its size did not decrease with distance…

The Eye of Japetus had blinked, as if to remove and irritating speck of dust. David Bowman had time for just one broken sentence, which the waiting men in mission control, nine hundred million miles away, were never to forget:

“The thing’s hollow—it goes on forever—and—oh my God—it’s full of stars!”

Instead of filling the monolith with another universe, Kubrick offered a collection of intriguing but really rather odd images that may be interpreted, or not interpreted, any way you like. It is the creator’s right to offer his audience freedom of choice. Bowman grows old in a strange, clinical but old-fashioned environment. Clarke more carefully plots the means by which Bowman is taken beyond the end of his life to be reborn as a higher form of intelligence, the star-child. Here, Kubrick and Clarke come back together, only while the movie star-child merely contemplates the Earth, the literary one detonates the orbiting weapons and destroys the now redundant humanity.