There was a landrover with a wire cage fitted on the tray into which we three prisoners were loaded and conveyed to the prison. In fact we had no idea where we were going, but it was far to the south and took most of a day. There were stops for toilets and hamburgers and coke which we had to achieve wearing handcuffs, but the weather was noticeably growing cooler. There were two drivers and two guards, but none of them were allowed to speak to us. Only when we arrived were we told that this was Holdsworthy Military Prison, just outside Sydney, the subject of many nightmares.

Michaels shrugged, “I am sceptical. If he extends both miniaturisation intensity and miniaturisation duration that can only be at the expense of something else, but for the life of me I can’t imagine what that something else might be. Perhaps that only means I am not a Benes. In any case, he says he can do it and we cannot take the chance of not believing him.”

They had come to the top of the escalator and Michaels had paused briefly there to complete his remark. Now he moved back to take a second escalator up another floor.

“Now, Grant, you can understand what we must do—save Benes. Why we must do it—for the information he has. And how we must do it—by miniaturisation.”

“Why by miniaturisation?”

“Because the brain clot cannot be reached from the outside. I told you that. So we will miniaturise a submarine, inject it into an artery, and with Captain Owens at the controls and with myself as pilot, journey to the clot. There, Duval and his assistant, Miss Peterson, will operate.”

Grant’s eyes opened wide. “And I?”

“You will be along as a member of the crew. General supervision, apparently.”

Grant said, violently, “Not I. I am not volunteering for any such thing. Not for a minute.”

Since Jules Verne, science fiction has always pranced along at the head of science, shining lights on the possible ways that might be travelled as much as the impossible routes. As science gained increasing precision, so did the fictions. It has always been true of the literature—just as much as the low literary skills have been outshone by the sci-fi writer’s extraordinary ideas, with a couple of remarkable exceptions. H. G. Wells remains the only truly great writer to dabble in the genre, although John Wyndham and Ray Bradbury cannot be ignored from a serious literary point of view. The masterpieces of Orwell and Huxley are technically speculative philosophy, not sci-fi.

The better the writer, the poorer the subject-matter is an adage that has always haunted literature, and for the most part it remains true. Brilliantly written books on fascinating subjects remain rare, and we cherish those few instances when it was achieved in the deepest part of our being. It is odd then, amongst a number of oddities, that science fiction movies followed suit for entirely different reasons. The sci-fi films of the 40s, 50s and early 60s generally combine great ideas with weak storytelling, shoddy production values and dreadful acting. The reason was obvious—the expense involved in doing them well was prohibitive, especially when the potential audience, while devoted, was small.

Then came the giant leap, in 1968, to 2001:A Space Odyssey, and science fiction has soared ever since, both in big-budget movies and high volume book sales and the two men who made that leap, in both forms, were Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov.

I have been looking at all science fiction that came my way before the mighty achievement of Clarke and Stanley Kubrick, and I arrive now at the transitional stage, more or less. Only two movies defied the odds, matching the best special effects possible at the time with fine acting and strong movie-making technique. The first was the Disney version of 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, and the other, twelve years later, was Fantastic Voyage. (I put aside the remarkable George Pal-HG Wells films and certain other heroic efforts—King Kong, Karloff’s Frankenstein, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Forbidden Planet and a few more— as outstanding achievements given their limitations—no excuses were required for the two movies I name.)

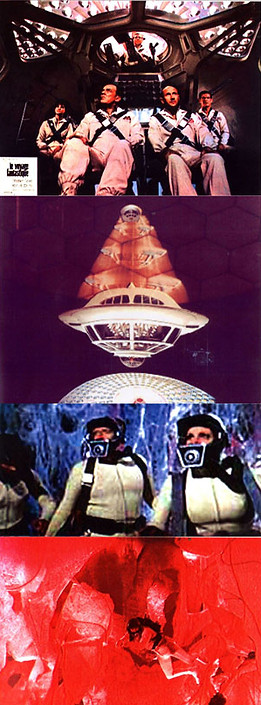

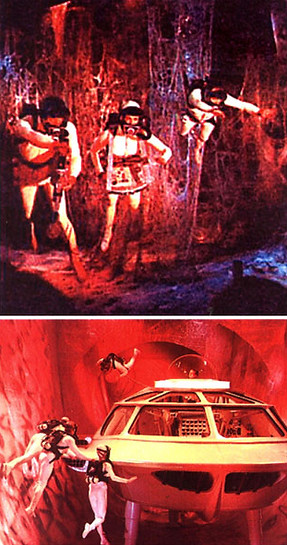

We dealing with the remarkable 1966 piece Fantastic Voyage here. The original story was by Jerome Bixby who was responsible for many episodes of Star Trek, The Twilight Zone and some rather poorer sci-fi films, and the screenplay by David Duncan, with an equally long list of bad sci-fi but the shining light of The Time Machine screenplay. Richard Fleischer, who directed 20,000 Leagues under the Sea and many of my other favourite films (Violent Saturday, Barabbas, The Vikings) and had many more to come, here did his usual brilliant job. The film was so stunningly original and cleverly put together that Isaac Asimov agreed to write the enthusiastic novelisation, an extraordinary concession for a writer of his stature. Although the book and movie mirror each other completely, in the film Grant’s three sentence reaction quoted above becomes, on the lips of actor Stephen Boyd one simple line—”But I don’t want to be miniaturised!”

The tale of the voyage through the human body in a blood-cell sized submarine reads and views with stunning conviction and is one of the true wonders. The visualisation of the world within us was both glorious and realistic, the cast strong, and the story equipped with gripping suspense. The desperate days for science fiction were all but left behind in this single sweep of the imaginative hand.

The film is not without its weaknesses—we could have managed without the clichéd argument as to whether a female should be involved in so dangerous a mission (Raquel Welsh is there mostly to scream and be rescued), and that the white corpuscles could have so completely devoured the miniturised submarine before there would be no ill effects of its growing back to full size inside the patient, needed to be set aside. But these are mere quibbles—the whole business was done with enormous skill and power, two years before 2001: A Space Odyssey changed everything, and to watch it now it is impossible to believe it was made so many decades ago, from which perspective the future lay just as far ahead of us as it did then. But the idea certainly does not seem quite so far-fetched as it did at the time. True movie greatness in action.